Why We Think What We Think

The unexpected origins of our deepest beliefs

We would love to believe our opinions are forged by evidence and reason. In part they are, but in much greater part they are not…

Based on years of research speaking with the world’s top neuroscientists, behavioural psychologists, social scientists and philosophers, Why We Think What We Think explores the unexpected origins of our beliefs.

If we hold some of our deepest beliefs purely as a matter of circumstance, how can we trust our own opinions, how can we know how to act, and how do we engage with the ideas of those we disagree with?

“Fascinating, incredibly valuable and accessible – a compelling view of why we see the world and each other the way we do.”

Prof. Bobby Duffy, bestselling author of The Perils of Perception

About the book.

Why have humans evolved to disagree?

Are our views really ours if we don’t consciously choose them?

And if the world feels more divided than ever, is that entirely a bad thing?

Without knowing it, almost all our opinions – whether we believe in God or in ghosts, our views on sex or animal rights or immigration, our basic sense of what’s right – are shaped by an astounding web of hidden forces. The age-old idea that our views are forged by reason and evidence alone is wrong: we are influenced by everything from the quirks of distant history, through the lines of our genetic code, to the geology of where we grew up.

This eye-opening book takes us on an unforgettable journey through culture, biology, geography, history, psychology and much more to uncover the hidden DNA of our opinions. It reveals:

Why the descendants of rice farmers have fundamentally different social values to the descendants of grain farmers

How our physical appearance shapes the way we see the world – and why conventionally attractive people tend to support the free market

Why liberals are more likely than conservatives to think pineapple should go on pizza – and why conservatives prefer smooth peanut butter to crunchy

How MRI scans can predict our voting preferences

Why hot and humid countries favour authoritarian leaders – and drought-prone countries prefer authoritarian gods.

Packed with surprising stories and counterintuitive discoveries, Why We Think What We Think does more than reveal how our beliefs are formed. By showing where our beliefs really come from, it invites us to step outside our own assumptions – and learn how to think more clearly, and more generously, about the world we all share.

What People are saying

Sneak Peek

-

Peanut Butter Politics

One of the more peculiar sets of correlations we discovered on Parlia, where we polled people’s views, was between politics and food preferences. Liberals, for example, seem to be the biggest tea-drinkers. Hard-left and hard-right prefer wine, where centrists much prefer beer. Centrists, unlike anyone else, will also often bite ice cream. Conservatives prefer a hamburger, whereas liberals prefer a curry. Conservatives are less likely than liberals to like spicy foods. Strangest of all: people on the right are measurably more likely than people on the left to prefer their peanut butter smooth.

Some of those differences can surely be explained by class or generation or some other factor. We measured a left-wing skew for tea over coffee - perhaps because tea, in the UK at least, is traditionally a working-class drink. But what do we do with the peanut butter? If you’re feeling poetic - and many polling analyses do feel more poetic than scientific - you might imagine it has something to do with the conservative concern with purity, so smooth and unblemished is preferable to lumpy and differentiated. Or perhaps it’s about tradition. You might argue crunchy peanut butter is a degenerate spin-off from the original product. But honestly...?

It turns out that the politics/food preference correlation has been widely studied. Pollsters have long noticed there was a connection, and deeply unpleasant organisations like Cambridge Analytica had used elements of it in their political targeting during Trump’s election victory over Clinton in 2016. If someone had been to an Indian or Mexican restaurant in the last month, it was a pretty good predictor they were a Democrat.

Why don’t Republicans go to Indian or Mexican restaurants? Is it racism? Is it distrust of novelty? Is it because Indian and Mexican chefs don’t set up shop in Republican districts?

Possibly all of the above. Could it also be because, for some reason, people who tend to vote Republican also actually tend not to like that kind of food?

In 2020, a paper came out of Cornell University that asked whether ‘gustatory sensitivity’, how sensitive your taste buds are, might predict your politics. Sure enough, they found that high ‘fungiform papilla density’, or high taste bud density on the tongue, predicts conservatism.

Some Republicans might well be racist, and distrust new experiences, and suffer from an absence of exotic cuisine in their neighbourhoods, but as our Parlia poll had already hinted at, they might also just be more physically reactive to spicy flavours.

Read more in Chapter 4 - The Body Politic: pretty privilege, the conservative brain complex, and what peanut butter can teach you about politics -

In 2022, Mediaeval England voted Macron

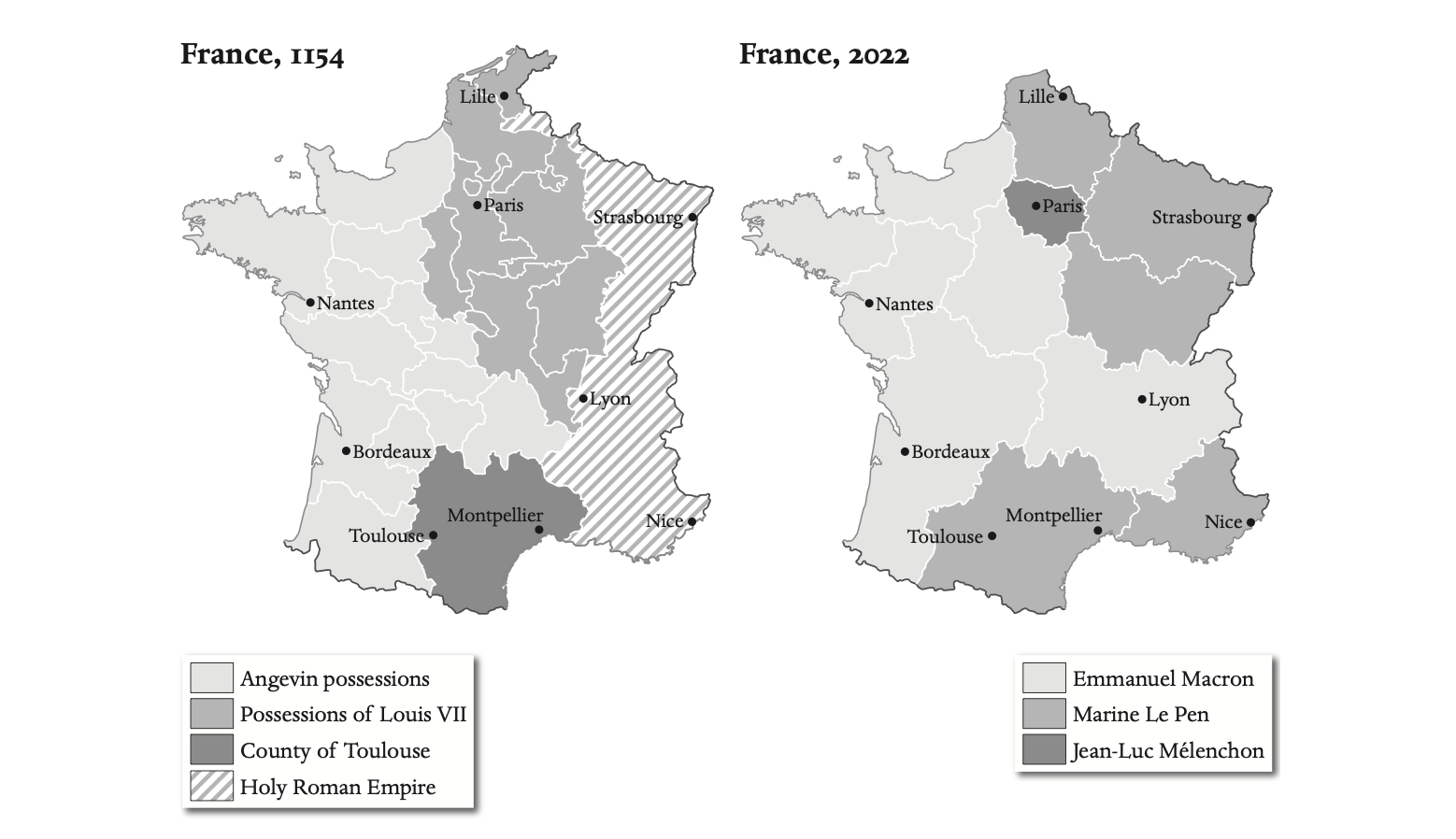

There is a surprising similarity between historic English territories in France and the voting map of the last French presidential elections.

On the surface it seems absurd that the English occupation of medieval France might have even the faintest resonance a thousand years later at the ballot box. But Anglo- Angevin culture (Henry II of England was the son of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou) was strikingly different from that of its neighbour over the Channel, and the English maintained a physical presence there for over 300 years. Medieval Britain was a more egalitarian society than medieval France – we can tell from the difference in life expectancy of the rich and poor, which was much more accentuated in France. By the thirteenth century, England was edging very slowly towards a constitutional monarchy, especially after the signing of Magna Carta in 1215 when the English barons forced King John to confirm the Charter of Liberties that limited his powers; France, on the other hand, would drift in the opposite direction, towards an absolute monarchy. Women in England had more rights and social opportunities – particularly in marriage law. Historians trace the differences in attitudes between the more liberal, more egalitarian, more republican west of France and its more conservative, hierarchical and Catholic east to the influence of repeated British invasion and occupation throughout the Middle Ages, and the ideas and culture they spread there.

Similar observations have been made about Brittany – that strip of land jutting out from the French mainland in the north- west. Brittany has always been considered a little different. As late as the nineteenth century, social commentators noted how its women were socially, financially and sexually more independent, and society more egalitarian.

This peculiar Breton exceptionalism has its roots in the very distant past. Brittany was an important base for the comparatively egalitarian Vikings, who settled in France from the eighth century onwards. Viking women, for example, were able to divorce their husbands – inconceivable for medieval French-women of the interior. But the roots may go back further still.

Brittany was never properly conquered by the Romans. Roman culture was deeply patriarchal – far more so than the culture of the Gauls whom Julius Caesar subjugated – and Brittany was spared its influence. The region’s peculiar egalitarianism, noted even in the nineteenth century, may be a distant echo of their two- millennia- old resistance to the military campaigns of Julius Caesar.

Read more in Chapter 3 - Cultural Misunderstandings: Why we’re blind to our beliefs and why we’re still having arguments started by our ancestors

Pre-Order Now

FAQs

-

Munthe reveals that most political disagreements aren't really about facts but about deeper, invisible assumptions about how the world works—like whether people are naturally good or selfish, or whether change is dangerous or necessary. By understanding these hidden foundations, readers can finally grasp why that relative at Thanksgiving seems to live in a completely different reality and learn strategies for more productive conversations.

-

The book provides a framework for recognizing the philosophical "languages" different people speak when discussing politics, helping readers translate between worldviews rather than talking past each other. Munthe offers concrete examples of how to find common ground by identifying shared values beneath surface disagreements, making it easier to maintain relationships across political differences.

-

Munthe explains how algorithms and media bubbles don't just show us different facts—they reinforce entirely different ways of thinking about what matters and what's possible in society. The book demonstrates how understanding these echo chambers as philosophical bubbles, not just information bubbles, can help readers break free from toxic polarization and engage more thoughtfully with different perspectives.

-

By revealing that political differences often stem from philosophical worldviews rather than moral failings or stupidity, the book helps readers depersonalize political conflict and reduce the emotional toll of polarization. Munthe's approach transforms frustrating political disagreements into fascinating puzzles about human thinking, offering readers relief from the exhausting assumption that the "other side" is simply evil or ignorant.

-

Turi Munthe explores how political ideologies function as comprehensive belief systems that filter how we interpret reality, from economic policies to social values. The book reveals how our political thinking is influenced by deeper philosophical assumptions about human nature, society, and morality that we often don't consciously examine.

-

The book examines how left and right political thinking diverge on fundamental questions about equality versus hierarchy, collective responsibility versus individual freedom, and whether human nature is malleable or fixed. Munthe traces these differences back to contrasting philosophical traditions and shows how they manifest in contemporary political debates about everything from taxation to identity politics.

-

Munthe argues that political polarization stems from people operating within incompatible philosophical frameworks that lead to fundamentally different interpretations of the same facts and events. The book demonstrates how these competing worldviews create parallel realities where opposing sides literally cannot understand each other's reasoning, making compromise increasingly difficult in democratic societies.

-

The book traces contemporary political ideologies back to Enlightenment thinkers, examining how liberal democracy draws from Locke and Mill, socialism from Marx and Rousseau, and conservatism from Burke and Oakeshott. Munthe shows how these historical philosophical debates about reason, tradition, and human progress continue to shape today's political arguments about freedom, justice, and the role of government.